Click text for more info

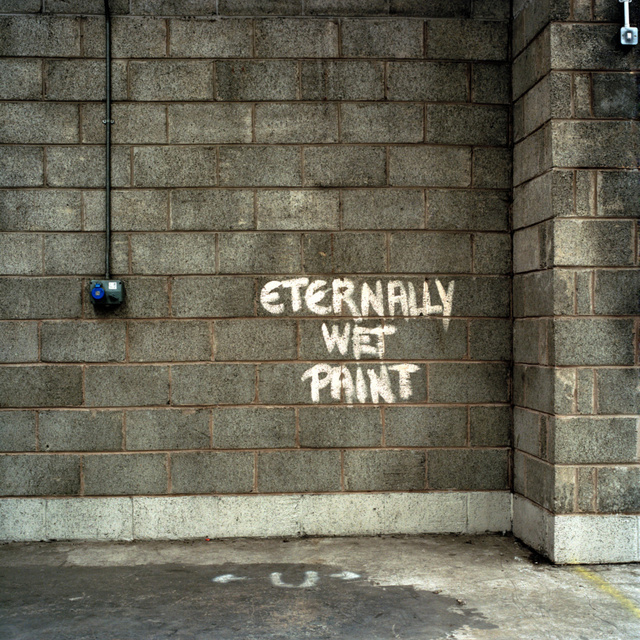

Interface This collection of photographs explores the regeneration of the land that lies alongside interfaces in Belfast. An interface is a Northern Irish term defined as: _‘The boundary between Catholic (Nationalist) and Protestant (Unionist) areas, especially where two highly segregated areas are situated close to each other, are known as interface areas. In many such areas of Belfast the interface is marked by a physical barrier known as a “peaceline”.’_ (http://cain.ulst.ac.uk) Eighty percent of those who were killed in Belfast during the conflict were within 500m of a peaceline. These locations had acted as some of the worst battlegrounds and were continuing to act as a focus for violence in Northern Ireland. The areas closest to the inversely named ‘peacelines’ are still the most dangerous parts of Northern Ireland. The British army arrived in Northern Ireland as a peacekeeping force in 1969. Following numerous attacks on homes in West Belfast, local communities had set up protective barricades. The army quickly replaced these existing barricades with barbed wire structures. Lieutenant General Sir Ian Freeland is often quoted: _‘The peace line will be a very, very temporary affair. We will not have a Berlin Wall or anything like that in this city.’_ Yet Belfast’s peacelines have far outlasted the Berlin Wall and there are now estimated to be up to thirty miles of dividing walls throughout North and West Belfast. None of these walls are planned to come down and the wall was built higher in certain locations this summer. Local residents have been surveyed on the issue and, whilst the vast majority would like them to come down in the future, not a single individual believed that their community was ready to live without a protecting barrier. There are complex borders between communities. The longest peaceline runs three miles long and divides the Shankill Road from the Lower Falls Road, yet other walls are much shorter, encircling and splitting communities in a more problematic series of divisions. In other locations interfaces are invisible: an underground wall in a cemetery dividing the dead; the Westlink motorway; two bus stops at the same location for different communities. Walking along these dividing lines I became interested in the way that land was being used on either side of the interfaces. In some areas, particularly in North Belfast, the division is extreme: facing back gardens are cut in two, a soaring corrugated metal wall slicing rows of terraced house apart. In other areas the presence of the wall has led to entire housing estates emptying, either through individual choice or government policy. This leaves behind a void beside the interface, and the wastelands are left as buffer zones, a further layer of protection or division between communities. Those who remain in these areas are often less socially mobile- the elderly, or the benefit dependent. Residents of interface areas are twice as likely to be unemployed, twice as likely to be on low incomes, and six times less likely to have A-level education than the rest of Northern Ireland. In terms of conflict transformation it is integral to address these areas and enforce change at a grassroots level - nothing will change if those who have been most affected are ignored. The Belfast Regeneration Office is in charge of an extensive renewal and development project throughout the city, particularly in the most deprived areas of North and West Belfast where the streets bear the burden of recent history and the violence continues. The need for new employment opportunities in these areas is key. Belfast was one of the world’s great industrial cities; at one time there were over fifty functioning mills, as well as the famous Harland and Wolff shipyards. Since the sixties, a lack of employment opportunities has been an important issue, the conflict adding an extra layer of complexity to the problems of de-industrialisation. The idea of economic regeneration was written into the Good Friday Agreement (1998): _‘Pending the devolution of powers to a new Northern Ireland Assembly, the British Government will pursue broad policies for sustained economic growth and stability in Northern Ireland and for promoting social inclusion…’._ The government has encouraged engineering companies to set up in Belfast with financial incentives, and new industries such as call centres have also proved successful. The Belfast Regeneration Office has purposefully placed many of these factories and companies at interface areas. This creates jobs within the most deprived areas but also has a number of more complex effects. The wastelands alongside the walls have already acted as a buffer zone, but redeveloping these sites into business parks neutralizes them further still. In many ways these sites act as security installations creating yet another barrier between nationalist/republican and unionist/loyalist communities: The sites themselves are attractive to businesses because of their location relatively close to the city centre. Invest Northern Ireland also rents the spaces at a reduced rate to further encourage tenants. This rezoning from residential to industrial is considered by some to be problematic. Due to a rising population within Republican areas there is high demand for social housing, some argue that this land could be better used for residential regeneration. The business parks could be placed along arterial routes further out of town, as in most cities. Furthermore a high proportion of the residential regeneration that is happening is not for social housing. Former mills are being converted into warehouse apartments and there are fears of gentrification as young professionals move into flats that are deemed too expensive for the local community. There also exists a clear need for mixed housing, whereby members of both the nationalist/republican and unionist/loyalist communities could live side by side, thereby beginning a process of mutual understanding and mixed community involvement within the most conflict affected areas of Belfast. This project consider how planners are manipulating the spaces around interface areas, trying to make sites that are historically territorial into neutral spaces. I am interested in how these newly created landscapes function: as a pretence of normality; as neutral spaces that become devoid of meaning for anyone; or as a complex resolution to the continuing issue of contested space in Belfast. Blanks spaces created by the conflict are being in-filled, a new burgeoning economy is being used as a buffer to drive post-conflict Belfast forwards. Yet these new spaces could be anywhere, they are placeless visions of a distant utopia far removed from the reality of a city blighted by sectarian divides. Ten years after the peace process in Northern Ireland began, these photographs aim to explore, investigate and illuminate a small part of the complexity of peace. Henrietta Williams, 2008